PPARGC1A

| PPARGC1A | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | PPARGC1A, LEM6, PGC-1(alpha), PGC-1v, PGC1, PGC1A, PPARGC1, PGC-1alpha, PPARG coactivator 1 alpha, PGC-1α | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

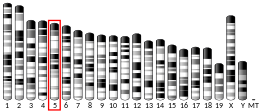

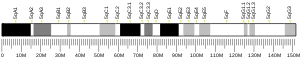

| External IDs | OMIM: 604517 MGI: 1342774 HomoloGene: 7485 GeneCards: PPARGC1A | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha (PGC-1α) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PPARGC1A gene.[4] PPARGC1A is also known as human accelerated region 20 (HAR20). It may, therefore, have played a key role in differentiating humans from apes.[5]

PGC-1α is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis.[6][7][8] PGC-1α is also the primary regulator of liver gluconeogenesis, inducing increased gene expression for gluconeogenesis.[9]

Function

PGC-1α is a gene that contains two promoters, and has 4 alternative splicings. PGC-1α is a transcriptional coactivator that regulates the genes involved in energy metabolism. It is the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis.[6][7][8] This protein interacts with the nuclear receptor PPAR-γ, which permits the interaction of this protein with multiple transcription factors. This protein can interact with, and regulate the activity of, cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) and nuclear respiratory factors (NRFs) [citation needed]. PGC-1α provides a direct link between external physiological stimuli and the regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis, and is a major factor causing slow-twitch rather than fast-twitch muscle fiber types.[10]

Endurance exercise has been shown to activate the PGC-1α gene in human skeletal muscle.[11] Exercise-induced PGC-1α in skeletal muscle increases autophagy[12][13] and unfolded protein response.[14]

PGC-1α protein may also be involved in controlling blood pressure, regulating cellular cholesterol homeostasis, and the development of obesity.[15]

Regulation

PGC-1α is thought to be a master integrator of external signals. It is known to be activated by a host of factors, including:

- Reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species, both formed endogenously in the cell as by-products of metabolism but upregulated during times of cellular stress.

- Fasting can also increase gluconeogenic gene expression, including hepatic PGC-1α.[16][17]

- It is strongly induced by cold exposure, linking this environmental stimulus to adaptive thermogenesis.[18]

- It is induced by endurance exercise[11] and recent research has shown that PGC-1α determines lactate metabolism, thus preventing high lactate levels in endurance athletes and making lactate as an energy source more efficient.[19]

- cAMP response element-binding (CREB) proteins, activated by an increase in cAMP following external cellular signals.

- Protein kinase B (Akt) is thought to downregulate PGC-1α, but upregulate its downstream effectors, NRF1 and NRF2. Akt itself is activated by PIP3, often upregulated by PI3K after G protein signals. The Akt family is also known to activate pro-survival signals as well as metabolic activation.

- SIRT1 binds and activates PGC-1α through deacetylation inducing gluconeogenesis without affecting mitochondrial biogenesis.[20]

PGC-1α has been shown to exert positive feedback circuits on some of its upstream regulators:

- PGC-1α increases Akt (PKB) and Phospho-Akt (Ser 473 and Thr 308) levels in muscle.[21]

- PGC-1α leads to calcineurin activation.[22]

Akt and calcineurin are both activators of NF-kappa-B (p65).[23][24] Through their activation, PGC-1α seems to activate NF-kappa-B. Increased activity of NF-kappa-B in muscle has recently been demonstrated following induction of PGC-1α.[25] The finding seems to be controversial. Other groups found that PGC-1s inhibit NF-kappa-B activity.[26] The effect was demonstrated for PGC-1 alpha and beta.

PGC-1α has also been shown to drive NAD biosynthesis to play a large role in renal protection in acute kidney injury.[27]

Clinical significance

Recently PPARGC1A has been implicated as a potential therapy for Parkinson's disease conferring protective effects on mitochondrial metabolism.[28]

Moreover, brain-specific isoforms of PGC-1alpha have recently been identified which are likely to play a role in other neurodegenerative disorders such as Huntington's disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.[29][30]

Massage therapy appears to increase the amount of PGC-1α, which leads to the production of new mitochondria.[31][32][33]

PGC-1α and beta has furthermore been implicated in polarization to anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages by interaction with PPAR-γ[34] with upstream activation of STAT6.[35] An independent study confirmed the effect of PGC-1 on polarisation of macrophages towards M2 via STAT6/PPAR gamma and furthermore demonstrated that PGC-1 inhibits proinflammatory cytokine production.[36]

PGC-1α has been recently proposed to be responsible for β-aminoisobutyric acid secretion by exercising muscles.[37] The effect of β-aminoisobutyric acid in white fat includes the activation of thermogenic genes that prompt the browning of white adipose tissue and the consequent increase of background metabolism. Hence, the β-aminoisobutyric acid could act as a messenger molecule of PGC-1α and explain the effects of PGC-1α increase in other tissues such as white fat.

PGC-1α increases BNP expression by coactivating ERRα and / or AP1. Subsequently, BNP induces a chemokine cocktail in muscle fibers and activates macrophages in a local paracrine manner, which can then contribute to enhancing the repair and regeneration potential of trained muscles.

Most studies reporting effects of PGC-1α on physiological functions have used mouse models in which the PGC-1α gene is either knocked out or overexpressed from conception. However, some of the proposed effects of PGC-1α have been questioned by studies using inducible knockout technology to remove the PGC-1α gene only in adult mice. For example, two independent studies have shown that adult expression of PGC-1α is not required for improved mitochondrial function after exercise training.[38][39] This suggests that some of the reported effects of PGC-1α are likely to occur only in the developmental stage.

Interactions

PPARGC1A has been shown to interact with:

- CREB-binding protein[40]

- Estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRα),[41] estrogen-related receptor beta (ERR-β), estrogen-related receptor gamma (ERR-γ).

- Farnesoid X receptor[42]

- FBXW7[43]

- MED1,[44] MED12,[44] MED14,[44] MED17,[44]

- NRF1[45]

- Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma[40][44]

- Retinoid X receptor alpha[46]

- Thyroid hormone receptor beta[47]

ERRα and PGC-1α are coactivators of both glucokinase (GK) and SIRT3, binding to an ERRE element in the GK and SIRT3 promoters.[citation needed]

See also

- MB-3 (drug)

- PPARGC1B

- Transcription coregulator

References

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029167 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Esterbauer H, Oberkofler H, Krempler F, Patsch W (Feb 2000). "Human peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 (PPARGC1) gene: cDNA sequence, genomic organization, chromosomal localization, and tissue expression". Genomics. 62 (1): 98–102. doi:10.1006/geno.1999.5977. PMID 10585775.

- ^ Pollard KS, Salama SR, Lambert N, Lambot MA, Coppens S, Pedersen JS, Katzman S, King B, Onodera C, Siepel A, Kern AD, Dehay C, Igel H, Ares M, Vanderhaeghen P, Haussler D (September 2006). "An RNA gene expressed during cortical development evolved rapidly in humans" (PDF). Nature. 443 (7108): 167–72. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..167P. doi:10.1038/nature05113. PMID 16915236. S2CID 18107797.

- ^ a b Valero T (2014). "Mitochondrial biogenesis: pharmacological approaches". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (35): 5507–9. doi:10.2174/138161282035140911142118. hdl:10454/13341. PMID 24606795.

Mitochondrial biogenesis is therefore defined as the process via which cells increase their individual mitochondrial mass [3]. ... This work reviews different strategies to enhance mitochondrial bioenergetics in order to ameliorate the neurodegenerative process, with an emphasis on clinical trials reports that indicate their potential. Among them creatine, Coenzyme Q10 and mitochondrial targeted antioxidants/peptides are reported to have the most remarkable effects in clinical trials.

- ^ a b Sanchis-Gomar F, García-Giménez JL, Gómez-Cabrera MC, Pallardó FV (2014). "Mitochondrial biogenesis in health and disease. Molecular and therapeutic approaches". Curr. Pharm. Des. 20 (35): 5619–5633. doi:10.2174/1381612820666140306095106. PMID 24606801.

Mitochondrial biogenesis (MB) is the essential mechanism by which cells control the number of mitochondria.

- ^ a b Dorn GW, Vega RB, Kelly DP (2015). "Mitochondrial biogenesis and dynamics in the developing and diseased heart". Genes Dev. 29 (19): 1981–91. doi:10.1101/gad.269894.115. PMC 4604339. PMID 26443844.

- ^ Klein MA, Denu JM (2020). "Biological and catalytic functions of sirtuin 6 as targets for small-molecule modulators". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 295 (32): 11021–11041. doi:10.1074/jbc.REV120.011438. PMC 7415977. PMID 32518153.

- ^ Lin J, Wu H, Tarr PT, Zhang CY, Wu Z, Boss O, Michael LF, Puigserver P, Isotani E, Olson EN, Lowell BB, Bassel-Duby R, Spiegelman BM (2002). "Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres". Nature. 418 (6899): 797–801. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..797L. doi:10.1038/nature00904. PMID 12181572. S2CID 4415526.

- ^ a b Pilegaard H, Saltin B, Neufer PD (February 2003). "Exercise induces transient transcriptional activation of the PGC-1alpha gene in human skeletal muscle". J. Physiol. 546 (Pt 3): 851–8. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034850. PMC 2342594. PMID 12563009.

- ^ Vainshtein A, Tryon LD, Pauly M, Hood DA (2015). "Role of PGC-1α during acute exercise-induced autophagy and mitophagy in skeletal muscle". American Journal of Physiology. 308 (9): C710-719. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00380.2014. PMC 4420796. PMID 25673772.

- ^ Halling JF, Ringholm S, Nielsen MM, Overby P, Pilegaard H (2016). "PGC-1α promotes exercise-induced autophagy in mouse skeletal muscle". Physiological Reports. 4 (3): e12698. doi:10.14814/phy2.12698. PMC 4758928. PMID 26869683.

- ^ Wu J, Ruas JL, Estall JL, Rasbach KA, Choi JH, Ye L, Boström P, Tyra HM, Crawford RW, Campbell KP, Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ, Spiegelman BM (2011). "The unfolded protein response mediates adaptation to exercise in skeletal muscle through a PGC-1α/ATF6α complex". Cell Metabolism. 13 (2): 160–169. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2011.01.003. PMC 3057411. PMID 21284983.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: PPARGC1A peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma, coactivator 1 alpha".

- ^ Canettieri, G., Koo, S.-H., Berdeaux, R., Heredia, J., Hedrick, S., Zhang, X., & Montminy (2005). "Dual role of the coactivator TORC2 in modulating hepatic glucose output and insulin signaling". Cell Metabolism. 2 (5): 331–338. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2005.09.008. PMID 16271533.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Yoon, J. Cliff; Puigserver, Pere; Chen, Guoxun; Donovan, Jerry; Wu, Zhidan; Rhee, James; Adelmant, Guillaume; Stafford, John; Kahn, C. Ronald; Granner, Daryl K.; Newgard, Christopher B. (September 2001). "Control of hepatic gluconeogenesis through the transcriptional coactivator PGC-1". Nature. 413 (6852): 131–138. Bibcode:2001Natur.413..131Y. doi:10.1038/35093050. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 11557972. S2CID 11184579.

- ^ Liang H, Ward WF (December 2006). "PGC-1alpha: a key regulator of energy metabolism". Adv Physiol Educ. 30 (4): 145–51. doi:10.1152/advan.00052.2006. PMID 17108241. S2CID 835984.

- ^ Summermatter S, Santos G, Pérez-Schindler J, Handschin C (May 2013). "Skeletal muscle PGC-1α controls whole-body lactate homeostasis through estrogen-related receptor α-dependent activation of LDH B and repression of LDH A" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 (21): 8738–43. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.8738S. doi:10.1073/pnas.1212976110. PMC 3666691. PMID 23650363.

- ^ Rodgers JT, Lerin C, Haas W, Gygi SP, Spiegelman BM, Puigserver P (March 2005). "Nutrient control of glucose homeostasis through a complex of PGC-1alpha and SIRT1". Nature. 434 (7029): 113–8. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..113R. doi:10.1038/nature03354. PMID 15744310. S2CID 4380393.

- ^ Romanino K, Mazelin L, Albert V, Conjard-Duplany A, Lin S, Bentzinger CF, Handschin C, Puigserver P, Zorzato F, Schaeffer L, Gangloff YG, Rüegg MA (December 2011). "Myopathy caused by mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) inactivation is not reversed by restoring mitochondrial function". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108 (51): 20808–13. Bibcode:2011PNAS..10820808R. doi:10.1073/pnas.1111448109. PMC 3251091. PMID 22143799.

- ^ Summermatter S, Thurnheer R, Santos G, Mosca B, Baum O, Treves S, Hoppeler H, Zorzato F, Handschin C (January 2012). "Remodeling of calcium handling in skeletal muscle through PGC-1α: impact on force, fatigability, and fiber type" (PDF). Am. J. Physiol., Cell Physiol. 302 (1): C88–99. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00190.2011. PMID 21918181.

- ^ Viatour P, Merville MP, Bours V, Chariot A (January 2005). "Phosphorylation of NF-kappaB and IkappaB proteins: implications in cancer and inflammation" (PDF). Trends Biochem. Sci. 30 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2004.11.009. hdl:2268/1280. PMID 15653325.

- ^ Harris CD, Ermak G, Davies KJ (November 2005). "Multiple roles of the DSCR1 (Adapt78 or RCAN1) gene and its protein product calcipressin 1 (or RCAN1) in disease". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 (21): 2477–86. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5085-4. PMID 16231093. S2CID 7184948.

- ^ Olesen J, Larsson S, Iversen N, Yousafzai S, Hellsten Y, Pilegaard H (2012). Calbet JA (ed.). "Skeletal muscle PGC-1α is required for maintaining an acute LPS-induced TNFα response". PLOS ONE. 7 (2): e32222. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...732222O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032222. PMC 3288087. PMID 22384185.

- ^ Brault JJ, Jespersen JG, Goldberg AL (June 2010). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1alpha or 1beta overexpression inhibits muscle protein degradation, induction of ubiquitin ligases, and disuse atrophy". J. Biol. Chem. 285 (25): 19460–71. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.113092. PMC 2885225. PMID 20404331.

- ^ Tran MT, Zsengeller ZK, Berg AH, Khankin EV, Bhasin MK, Kim W, Clish CB, Stillman IE, Karumanchi SA, Rhee EP, Parikh SM (2016). "PGC1α drives NAD biosynthesis linking oxidative metabolism to renal protection". Nature. 531 (7595): 528–32. Bibcode:2016Natur.531..528T. doi:10.1038/nature17184. PMC 4909121. PMID 26982719.

- ^ Zheng B, Liao Z, Locascio JJ, Lesniak KA, Roderick SS, Watt ML, Eklund AC, Zhang-James Y, Kim PD, Hauser MA, Grünblatt E, Moran LB, Mandel SA, Riederer P, Miller RM, Federoff HJ, Wüllner U, Papapetropoulos S, Youdim MB, Cantuti-Castelvetri I, Young AB, Vance JM, Davis RL, Hedreen JC, Adler CH, Beach TG, Graeber MB, Middleton FA, Rochet JC, Scherzer CR (October 2010). "PGC-1{alpha}, A Potential Therapeutic Target for Early Intervention in Parkinson's Disease". Sci Transl Med. 2 (52): 52ra73. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3001059. PMC 3129986. PMID 20926834.

- ^ Soyal SM, Felder TK, Auer S, Hahne P, Oberkofler H, Witting A, Paulmichl M, Landwehrmeyer GB, Weydt P, Patsch W (2012). "A greatly extended PPARGC1A genomic locus encodes several new brain-specific isoforms and influences Huntington disease age of onset". Human Molecular Genetics. 21 (15): 3461–73. doi:10.1093/hmg/dds177. PMID 22589246.

- ^ Eschbach J, Schwalenstöcker B, Soyal SM, Bayer H, Wiesner D, Akimoto C, Nilsson AC, Birve A, Meyer T, Dupuis L, Danzer KM, Andersen PM, Witting A, Ludolph AC, Patsch W, Weydt P (2013). "PGC-1α is a male-specific disease modifier of human and experimental amyotrophic lateral sclerosis". Human Molecular Genetics. 22 (17): 3477–84. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddt202. PMID 23669350.

- ^ Crane JD, Ogborn DI, Cupido C, Melov S, Hubbard A, Bourgeois JM, Tarnopolsky MA (February 2012). "Massage therapy attenuates inflammatory signaling after exercise-induced muscle damage". Sci Transl Med. 4 (119): 119ra13. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3002882. PMID 22301554. S2CID 2610669.

- ^ Brown E (2012-02-01). "Study works out kinks in understanding of massage". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Videos | The Buck Institute for Research on Aging". Buckinstitute.org. Retrieved 2013-10-11.

- ^ Yakeu G, Butcher L, Isa S, Webb R, Roberts AW, Thomas AW, Backx K, James PE, Morris K (October 2010). "Low-intensity exercise enhances expression of markers of alternative activation in circulating leukocytes: roles of PPARγ and Th2 cytokines". Atherosclerosis. 212 (2): 668–73. doi:10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.07.002. PMID 20723894.

- ^ Chan MM, Adapala N, Chen C (2012). "Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-γ-Mediated Polarization of Macrophages in Leishmania Infection". PPAR Res. 2012: 796235. doi:10.1155/2012/796235. PMC 3289877. PMID 22448168.

- ^ Vats D, Mukundan L, Odegaard JI, Zhang L, Smith KL, Morel CR, Wagner RA, Greaves DR, Murray PJ, Chawla A (July 2006). "Oxidative metabolism and PGC-1beta attenuate macrophage-mediated inflammation". Cell Metab. 4 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.011. PMC 1904486. PMID 16814729.

- ^ Roberts LD, Boström P, O'Sullivan JF, Schinzel RT, Lewis GD, Dejam A, Lee YK, Palma MJ, Calhoun S, Georgiadi A, Chen MH, Ramachandran VS, Larson MG, Bouchard C, Rankinen T, Souza AL, Clish CB, Wang TJ, Estall JL, Soukas AA, Cowan CA, Spiegelman BM, Gerszten RE (2014). "β-Aminoisobutyric acid induces browning of white fat and hepatic β-oxidation and is inversely correlated with cardiometabolic risk factors". Cell Metabolism. 19 (1): 96–108. doi:10.1016/j.cmet.2013.12.003. PMC 4017355. PMID 24411942.

- ^ Ballmann C, Tang Y, Bush Z, Rowe GC (October 2016). "Adult expression of PGC-1α and -1β in skeletal muscle is not required for endurance exercise-induced enhancement of exercise capacity". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 311 (6): E928–E938. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00209.2016. PMC 5183883. PMID 27780821.

- ^ Halling JF, Jessen H, Nøhr-Meldgaard J, Buch BT, Christensen NM, Gudiksen A, Ringholm S, Neufer PD, Prats C, Pilegaard H (July 2019). "PGC-1α regulates mitochondrial properties beyond biogenesis with aging and exercise training". Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 317 (3): E513–E525. doi:10.1152/ajpendo.00059.2019. PMID 31265325. S2CID 195786475.

- ^ a b Puigserver P, Adelmant G, Wu Z, Fan M, Xu J, O'Malley B, Spiegelman BM (November 1999). "Activation of PPARgamma coactivator-1 through transcription factor docking". Science. 286 (5443): 1368–71. doi:10.1126/science.286.5443.1368. PMID 10558993.

- ^ Schreiber SN, Emter R, Hock MB, Knutti D, Cardenas J, Podvinec M, et al. (April 2004). "The estrogen-related receptor alpha (ERRalpha) functions in PPARgamma coactivator 1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-induced mitochondrial biogenesis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 101 (17): 6472–7. Bibcode:2004PNAS..101.6472S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308686101. PMC 404069. PMID 15087503.

- ^ Zhang Y, Castellani LW, Sinal CJ, Gonzalez FJ, Edwards PA (January 2004). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) regulates triglyceride metabolism by activation of the nuclear receptor FXR". Genes Dev. 18 (2): 157–69. doi:10.1101/gad.1138104. PMC 324422. PMID 14729567.

- ^ Olson BL, Hock MB, Ekholm-Reed S, Wohlschlegel JA, Dev KK, Kralli A, Reed SI (January 2008). "SCFCdc4 acts antagonistically to the PGC-1α transcriptional coactivator by targeting it for ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis". Genes Dev. 22 (2): 252–64. doi:10.1101/gad.1624208. PMC 2192758. PMID 18198341.

- ^ a b c d e Wallberg AE, Yamamura S, Malik S, Spiegelman BM, Roeder RG (November 2003). "Coordination of p300-mediated chromatin remodeling and TRAP/mediator function through coactivator PGC-1alpha". Mol. Cell. 12 (5): 1137–49. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00391-5. PMID 14636573.

- ^ Wu Z, Puigserver P, Andersson U, Zhang C, Adelmant G, Mootha V, Troy A, Cinti S, Lowell B, Scarpulla RC, Spiegelman BM (1999). "Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1". Cell. 98 (1): 115–24. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80611-X. PMID 10412986. S2CID 16143809.

- ^ Delerive P, Wu Y, Burris TP, Chin WW, Suen CS (February 2002). "PGC-1 functions as a transcriptional coactivator for the retinoid X receptors". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (6): 3913–7. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109409200. PMID 11714715.

- ^ Wu Y, Delerive P, Chin WW, Burris TP (March 2002). "Requirement of helix 1 and the AF-2 domain of the thyroid hormone receptor for coactivation by PGC-1". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (11): 8898–905. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110761200. PMID 11751919.

Further reading

- Knutti D, Kralli A (2001). "PGC-1, a versatile coactivator". Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 12 (8): 360–5. doi:10.1016/S1043-2760(01)00457-X. PMID 11551810. S2CID 24230985.

- Puigserver P, Spiegelman BM (2003). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha): transcriptional coactivator and metabolic regulator". Endocr. Rev. 24 (1): 78–90. doi:10.1210/er.2002-0012. PMID 12588810.

- Soyal S, Krempler F, Oberkofler H, Patsch W (2007). "PGC-1alpha: a potent transcriptional cofactor involved in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes". Diabetologia. 49 (7): 1477–88. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0268-6. PMID 16752166.

- Handschin C, Spiegelman BM (2007). "Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 coactivators, energy homeostasis, and metabolism". Endocr. Rev. 27 (7): 728–35. doi:10.1210/er.2006-0037. PMID 17018837.

External links

- PPARGC1A protein, human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- NURSA C110

- FactorBook PGC1A

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: Q9UBK2 (Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

- v

- t

- e

- Chromatin Structure Remodeling (RSC) Complex

- SWI/SNF